Can Nike keep its cool?

As a child growing up in the Democratic Republic of Congo, Gloire Ndongala didn’t know much about the wider world, with one exception: he adored US basketball star Michael Jordan. “Think about it, in the Congo we had hardly any technology back then, and we still heard of Michael Jordan,” Ndongala says.

The Chicago Bulls legend’s accomplishments on the court were transcendent but his style was accessible, thanks to the flashy Nike shoes, named for him, which he wore while making gravity-defying dunks.

To Ndongala, now a 32-year-old author, owning a pair of Jordans was more than just a way to emulate his favourite hoops player. When he eventually immigrated to the US, they became a cultural talisman that helped him connect with Americans. “It doesn’t matter if you’re black or white, because if you are wearing Jordans, there’s a commonality between you,” he says.

In 2010, Ndongala settled in Cut Bank, Montana, population 2,900. The brutal winters made him question his choice. “I had been thinking, ‘What am I doing in this town? There are hardly any African Americans out there,’” he says. But that year, Ndongala discovered Norman’s Sport & Western, a local store that sold an impressive selection of Jordan shoes: “When I found Norman’s, it was like, ‘Oh my goodness, I’m home.’”

Places like Norman’s are more than just sporting-goods stores. They were part of Nike’s earliest retail network, staking a physical foothold for the company when it was just beginning as a shoe distributor. “We supported Nike and Jordan when they weren’t even that cool,” says Teri Bickford, manager of Norman’s, which has now carried products with the iconic “swoosh” logo for more than 40 years. Today her shop is an outpost of the Nike brand in a community far from flagship stores or even the nearest large mall-based chain, 110 miles away.

But by the time Ndongala discovered Norman’s, mom-and-pop stores had been eclipsed as the driver of Nike sales by international chains and ecommerce. Instead of simply competing against other sports brands such as Adidas or Under Armour on the shelves at Foot Locker, Nike faced new rivals, including Lululemon, a yoga-pants specialist with its own store network, and, later, digital-first brands such as Outdoor Voices. Consumers no longer had to go to the mall to browse the latest gear.

“Our world is changing,” wrote then chief executive Mark Parker in Nike’s annual report in 2008. “The digital age is fuelling change at its fastest rate in history. Power is in the hands of consumers. They have near infinite choices and unlimited access to those choices . . . To be relevant, to be accepted, a company must bring its authentic self to market.”

As the digital landscape has continued to change at pace over the past decade, so too has the manner in which Nike has presented its “authentic self”. Synonymous with the “Just Do It” advertising campaign that began in 1988 (the first commercial told the story of Walt Stack, an 80-year-old who ran 17 miles each morning), Nike has always been a brand that stands for sport as self-empowerment. But it has also been quick to embrace growing movements for social justice, using its clout to signal support for causes such as the inclusion of girls in sport and the fight against HIV/Aids.

In recent times, however, navigating this course has become more hazardous. Companies are criticised both if they speak out on societal issues and if they don’t. As a new generation of consumers and employees makes itself heard, Nike has been called out for not living up to the messaging it broadcasts to the wider world.

“It’s been a tumultuous period for Nike,” says Trevor Edwards, the former brand president of the company who left in 2018. “It is so based on passion for sport, passion for the Nike brand, and that passion is starting to dissipate internally.”

The result is one of the most challenging moments in the company’s history. It must contend not only with a radical shift in retail strategies but also the wider cultural reckoning with the intersection of race, gender and power. In interviews with current and former employees, industry executives, consumers and retail partners, divisions emerge over how to tackle such issues while remaining true to the spirit that has set the brand apart from other sportswear manufacturers. One question looms above the rest: is it the end of an era for Nike?

As the world’s largest sportswear maker, Nike has outfitted some of the greatest athletes in history, including basketball star LeBron James, tennis champion Serena Williams and elite footballers Cristiano Ronaldo and Neymar. Its products are sold everywhere from family footwear chains to Parisian boutiques. And by positioning itself at the forefront of pop culture — Nike’s corporate HQ was the setting for a recent Drake music video — the brand cultivates an enduring image of being fashion-forward and universally cool.

It achieved this success through two distinguishing characteristics: its deep relationship with a diverse group of consumers and its authoritative marketing to them, typified by a 1993 campaign in which the tempestuous basketball star Charles Barkley defiantly told children: “I am not a role model.” But in recent years there has been a simmering power struggle within the company, which began as a haphazard distributor of Japanese running shoes in Oregon in 1964 and has since grown into a $37bn behemoth by revenue. The issue of who should lead Nike has laid bare questions surrounding its very essence: is it a marketing company that makes great shoes, or is it a shoe company that makes great ads?

After 25 years rising through the ranks, British executive Edwards was just one step from the top. The London-born son of Jamaican immigrants, he joined Nike’s marketing team in the early 1990s and made a career of the company’s evolution from simple sneaker maker to the Apple of sportswear: an ad-savvy, digital athletic brand. By late 2017, he oversaw all of Nike’s brand and was the heir apparent to Parker as chief executive.

But that succession plan seemingly didn’t sit well with Nike’s top footwear designer. Widely acclaimed for his pioneering design of some of the swoosh’s most iconic sneakers, including the Air Max and many Air Jordans, Tinker Hatfield is the archetype of a different kind of Nike executive, a veteran of its earliest days as a shoe brand made by runners, for runners. A native Oregonian, Hatfield trained as a college pole vaulter under Nike’s co-founder, athletics coach Bill Bowerman. Four decades later, he holds the lofty role of vice-president of creative concepts, reporting directly to the chief executive.

Despite their different backgrounds, Edwards and Hatfield weren’t known to have disagreements. So it caught some staff by surprise when Hatfield told colleagues, in the autumn of 2017, that he didn’t think Edwards should be put in charge of “an American brand”, according to Edwards and another person who worked at Nike at the time.

“When Tinker started making comments about [Edwards] openly, it was really shocking to people. You don’t say something like that, especially not about senior management,” says the former employee.

When he learnt of Hatfield’s remarks, Edwards says he called a meeting between them to address the matter. Describing their conversation as “cordially awkward”, he says he wanted to understand Hatfield’s point of view. “We were about serving athletes around the world, so this idea that Nike was an ‘American brand’ didn’t make sense.”

Through Nike, Hatfield declined a request for an interview but said in a statement that “at no point in that meeting or outside of it, I ever questioned [Edwards’] fitness to lead . . . My focus wasn’t on who will lead Nike in the future. My focus has been and continues to be on creating the best products [and] being a resource to my teammates.”

Reports of the strain between the two men revealed another brewing tension: between Nike’s white establishment — who had ties dating back to the 1970s — and its modern, diverse workforce, an extension of its customer base.

Edwards views the meeting between himself and Hatfield as emblematic of both the uneven power structure within Nike, which sometimes favoured those with the closest ties to the company founders, and “as part of being a black leader”. He perceives their exchange as an instance of discrimination, something he has faced throughout his career. “It was not a comfortable conversation, and I’m not someone who is easily offended,” he says, adding that he doesn’t dwell on the meeting and has moved on.

In his statement, Hatfield didn’t directly respond to questions seeking clarity on what he meant by “an American brand”, but said that “any inference to [Edwards’] ethnicity or nationality is entirely false” and that the conversation “ended with us shaking hands and agreeing to be more open with our communication and working better together”.

Nike’s path to the top of the sportswear world did not follow a straight line. After a brief sales downturn in the 1980s, company co-founder Phil Knight shifted priorities. “For years, we . . . put all our emphasis on designing and manufacturing the product,” he told Harvard Business Review in 1992. “But now we understand that the most important thing we do is market the product.”

That was the same year that Nike hired Edwards, then a brand executive at Colgate-Palmolive. Marketing became central to the company’s growth, and advertising more and more divorced from its actual products. By the mid-2000s, two of its most famous faces were Tiger Woods and Lance Armstrong: not because the swoosh was known for golf equipment or cycling clothes but because these athletes embodied Nike’s win-at-all-costs ethos.

When the time came to evolve for the digital era, executives again relied on marketing-derived insights and in 2008 reorganised all of Nike’s functions and services by sport. Running had its own marketing, sales, product-development and retail-account managers. So did basketball, football, sportswear and training. Edwards, who helped formulate the revamp, says that by orienting traditional retail functions towards specific sports, “the power is with the consumer, not any one department”. In other words, all Nike employees — not just marketers — would have a clearer sense of exactly which customer they were selling to.

“There’s a big difference between what a basketball player needs and a baseball player needs,” says Musa Tariq, who has worked at Ford, Apple and Airbnb and who directed social-media marketing across the sport categories at Nike from 2012 to 2014. “What makes Nike magical is that it has real athlete insight from each sport . . . I remember working with someone in the running category and the way he would write copy for an advertisement would be very specific to that culture.”

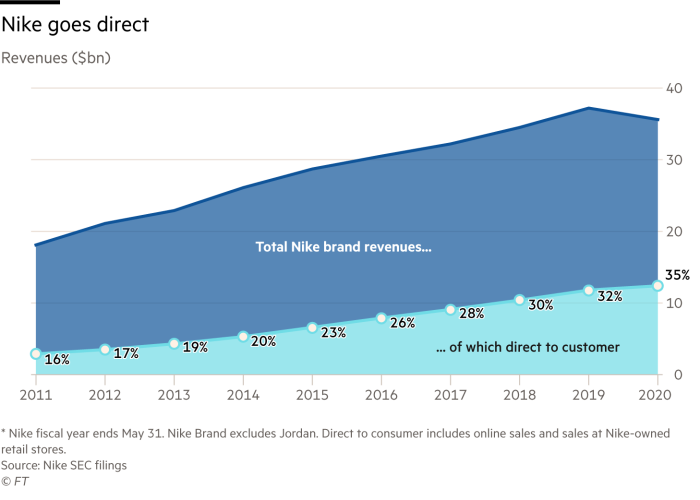

The strategy proved extremely successful. From 2008 to 2017, Nike’s annual revenues nearly doubled, from $18.6bn to $34.4bn. Along the way, it fostered growth for its digital endeavours: the running category, for example, developed and launched its own workout app, which is now Nike Run Club, enabling the company to glean a better idea of how its consumers behaved. “A runner wants more than just running shoes. They want a whole set of services,” Edwards says. “For us it went beyond just shopping, it was about how you consider the whole ideology of the consumer.”

In 2015, Nike launched the SNKRS app, perhaps the most consequential development in its relationship with consumers. Following Michael Jordan’s retirement from basketball, Air Jordans — as well as other Nike shoes — had become popular collector’s items. To stoke demand, Nike sold re-releases, or retros, mostly through limited-edition drops at established retail partners.

“From the mid-90s and before, you had to really be in the know in order to track down a pair of sneakers you wanted to buy,” says Howie Kahn, co-author of Sneakers, a 2017 book exploring the shoes’ cultural impact. “You had to be really tight with someone at a mom-and-pop store in order to get them.” But the SNKRS app enabled Nike to sell directly to consumers, spelling the beginning of the end for long-term retail partners.

A quintessential mom-and-pop retailer, Norman’s is situated in a one-traffic-light town. “People can’t always buy back-to-school clothes or shoes for their kids, so we’ll do things for our customers, like allow them to do a payroll deduction” to cover purchases in instalments, Bickford says. While her store carries other wares, such as cowboy boots and horse saddles, she attributes roughly 50 per cent of her sales to Jordans. “This is what our customer wants. People will go without their necessities to buy their children Jordans,” she says.

In 2017 Nike launched the next phase of its strategy, aimed at selling more online or in glitzy new stores of its own, mostly in big cities such as New York or Shanghai. “When they set this into motion, Nike had the desire to gain more control over their own distribution,” says Neil Schwartz, president of sports retail data analytics firm SBRnet.

The strategy also called for cutting out middlemen retailers who weren’t driving the bottom line. In late 2019, Bickford received a letter from her Nike sales representative, which informed her that “we have recently decided to narrow and focus distribution of Jordan Brand product. According to this allocation decision, Nike will no longer provide you with Jordan Brand product.”

“Does Nike care about the guy in Montana that sells 100, maybe 200 pairs a year? No,” says Schwartz. “They realise they could spend a fraction of what they were spending to service that account on digital advertising and get a bigger bang for their buck.”

Bickford says she can understand, from a sales perspective, why a store like Norman’s may not fit into Nike’s retail future. “We’re just a little fish in Nike’s big sea,” she says.

But looking at the bigger picture, she argues that Nike’s direct-sales strategy is at odds with how it markets itself as a champion of inclusiveness. Bickford does not have internet access at home — which is typical for residents in the Cut Bank area and the neighbouring Blackfeet Nation indigenous reservation, she says, leaving them effectively cut off from ecommerce. “Nike is always supposed to stand up for the underdog, they’re always on the news standing up for the people who are oppressed. So what are they doing here?” she asks.

A Nike spokesman, KeJuan Wilkins, says the company’s present network of retail partners is “as diverse as the marketplace itself”, including “smaller mom-and-pops that serve as authenticators of our brand”. But Ndongala, the longtime Norman’s customer, says the decision to cut off Jordan sales is a blow for those who, like him, forged a sense of local belonging through the store. Taking the Jordan account away, he says, “sends another message of neglect, for this community, and for the reservation, now that Jordan has become a part of the culture here”.

As Nike adjusted to the new retail landscape, events in the wider world were driving far-reaching changes both inside and outside the company. In 2016, Colin Kaepernick, a star quarterback for the San Francisco 49ers, began taking a knee before games to protest police brutality and racial inequality. The following year, the #MeToo movement took off after investigations into movie mogul Harvey Weinstein triggered a broad reckoning about gender and power.

Nike was not immune. In the first weeks of 2018, a group of female employees at the company circulated an informal survey to take stock of perceived inequalities and allegations of inappropriate behaviour in the workplace. The results were delivered to chief executive Parker.

What followed shocked many at Nike: on March 15, Parker sent a company-wide memo saying that he was investigating complaints of inappropriate conduct and that Edwards would resign immediately. “We’ve heard from strong and courageous employees,” Parker wrote. “This has been a very difficult time.”

The subsequent investigation precipitated the exit of nearly a dozen employees but, as a Nike spokesman said at the time, no direct allegations of inappropriate behaviour were ever levelled against Edwards. Edwards now says: “I was at Nike for over 25 years, and I had a track record without incident from the first day I was there to the last day I left. I never condoned a toxic work culture at Nike, and they made it clear to me at the time that there were never any allegations against me.”

In interviews both then and now, there has been little consensus among employees on whether Edwards was ultimately accountable for the culture problems outlined in the survey. But his departure unquestionably left a void in non-white leadership at the top of the Nike brand.

“Nike is a white, male, runner’s company,” says a former employee who described the Edwards-Hatfield spat, pointing to the company’s founding executives and longest-standing leaders. Co-founders Knight and Bowerman met at the University of Oregon athletics programme; Hatfield, another U of O athletics alumnus, joined in 1981; Parker, who ran at Penn State, joined in 1979 as one of its first footwear designers.

Edwards says that, in his experience, “there is an environment of certain privileges” at Nike for those with close ties to the company’s origins. “There’s an inner circle and outer circle, and it’s tough for black leaders to break in,” says another former employee, who is black and left Nike this year, frustrated with what they saw as a lack of sufficient action on diversity issues. “Trevor was our president, he had a culture of bringing people up, giving people opportunities.”

In 2017, just 16 per cent of Nike vice-presidents were non-white, according to the company. (By the end of 2019, that figure had risen to 21 per cent.) Tariq, the former social-media marketer, says that while the level of diversity he observed was roughly comparable to other major corporations he’s worked with, “there’s really no excuse at Nike, because they work with so many black athletes”.

The issue gained urgency as the company’s advertising took on an increasingly progressive tone. In late 2018, Nike rolled out what was arguably its most controversial commercial ever, a spot featuring Kaepernick and implicitly endorsing his stance denouncing racial injustice. “Believe in something, even if it means sacrificing everything,” said Kaepernick in the tagline, which triggered an initial consumer backlash and a sell-off of Nike shares (though they subsequently rebounded).

With the spot, Nike placed itself at the forefront of conversations about just how political consumer-facing companies should be, or whether they could engage in social-justice issues as an effective way to win customers. Long gone were the days of Michael Jordan’s neutrality — he once declined to make a political endorsement because “Republicans buy sneakers, too”.

The commercial won an Emmy but it also provoked plenty of cynicism. In a memorable scene from the recent BBC/HBO drama Industry, one character muses to African-American graduate trainee Harper: “We’re living in an era of ‘woke’ capitalism, right? I’m Nike, I pretend to care about black people. You pretend to hate capitalism and buy my trainers.”

By the end of the decade, the company’s succession planning — and its numbers — were in turmoil. Nike had told investors it planned to hit $16bn in sales directly to consumers by 2020; at the end of fiscal 2019, the figure was barely $12bn.

Around this time, Parker came under fire for his association with the now disbanded Nike Oregon Project, the company’s elite group of Olympic distance runners. In late 2019, the US Anti-Doping Agency levied four-year bans against Alberto Salazar and Jeffrey Brown, respectively the group’s coach and physician, for “orchestrating and facilitating prohibited doping conduct”. Arbitration documents related to the case revealed email correspondence indicating that Salazar and Brown kept Parker informed of some of the conduct in question.

Both Salazar and Brown have denied wrongdoing and are appealing. In a memo to employees at the time, Parker strongly condemned the agency’s findings and said “the very idea [of doping] makes me sick”. Three weeks after the controversy, Nike announced Parker would remain at the company but step down as chief executive and would be replaced by board member and former eBay chief John Donahoe.

Though Parker had previously said he would stay on as chief executive “beyond 2020”, he vigorously denied the succession announcement was connected to the doping case. Sandra Carreon-John, a company spokeswoman, says Parker continues to serve as Nike’s executive chairman, where he remains “an active member of Nike’s management team”.

Still, the appointment of Donahoe, a Silicon Valley veteran without Hatfield’s legacy in product design or Edwards’ decades of marketing experience, signalled a dramatic change at the very top of the sportswear industry.

Eric Liedtke, former director of global brands at rival Adidas, says Nike’s decision was similar to what happened when Adidas tapped Kasper Rorsted of consumer products giant Henkel to be its new chief executive in 2016. “These guys are professional operators, they’re not from sports, or even sports companies,” Liedtke says. “They just grind out results. It signals a change of culture, a change in dynamic of these companies.”

From his earliest meetings at Nike, it was clear Donahoe was going to shake things up. Six feet five, with a flat Midwestern accent, he brought a straightforward approach, rankling some insiders. He told employees he didn’t want to see any fancy PowerPoint presentations, preferring plain-text, black-and-white slides, according to two people familiar with the matter. “At Nike, your presentation skills are paramount,” says one. To eschew a practice that allowed employees to flaunt their creativity “was freaking anathema to the culture at Nike”. Wilkins, the company spokesman, says the remark was not a directive but simply a matter of “personal preference”.

Donahoe quickly made it clear that he had heard staff concerns about diversity. In February, he appointed a working group of senior black employees to evaluate diversity issues at the company. A member of the group says they believe Donahoe had been “surprised by some of the racial diversity and inclusion at Nike. I think he would have thought that Nike would be better [at this].”

Even as the question of how to make Nike into a modern, diverse, digital-first retailer came into focus, two world-altering events sharpened its urgency: the onset of the coronavirus pandemic and the surge of the Black Lives Matter movement.

By the summer of 2020, working from home was the new normal. Retail stores went through cascading shutdowns. During months of protests against racial injustice in the US, hastened by the police killings of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor, Nike’s hometown of Portland was the site of occasionally violent conflict. Against this backdrop, the brand’s challenges appeared starker than ever. Global revenues dropped 38 per cent as the company swung to a $790m loss in the quarter ended in May.

In June, Donahoe announced sweeping changes, tantamount to unravelling more than a decade of Nike’s retail revolution. He disbanded the focus on discrete sport categories and began reorienting all products under three divisions: men’s, women’s and kids’. “We know that our consumers don’t see themselves as only runners or yoga practitioners. They don’t think in terms of performance versus sportswear,” Donahoe told analysts. The reorganisation, which is ongoing, has led to hundreds of lay-offs.

The overhaul is a turning point for Nike as a retailer. Economic forces pushing the shift to direct sales have only intensified during the pandemic. But some question whether adopting a gender-based model, common at other big companies, will sacrifice some of Nike’s sport-specific marketing “magic”, as Tariq puts it. “That is what I am most curious to see — whether Nike can remain as relevant to their customers without [these categories],” he says. Another former employee believes the gendered approach “can work for sure, but you’re not going to be Nike any more. You’re not going to be cultural, you’re not going to have that specialness.”

One current employee says there has been some internal hand-wringing about the direct-selling strategy that has cut off retail accounts such as Norman’s. (Nike has reduced its network of “undifferentiated” retail partners by 30 per cent in the past three years.) “It’s definitely a risk to authenticity to axe these mom-and-pop shops.”

But the same employee believes that while Donahoe represents a breath of fresh air, he is also someone who has the ear of retired co-founder Knight. This closeness is likely to benefit members of the Nike establishment such as Hatfield, says the former employee who described the designer’s disagreement with Edwards. Amid significant restructuring, they say, it’s unlikely Donahoe would endanger his alliance with the founder: “He is not gonna piss off Phil, he’s Phil’s guy.”

Meanwhile, the broad reckoning over racial injustice has come closer to home. In August, a black apprentice designer at Nike, Simone Sullivan, spoke at a Portland protest to describe some of her frustrations, including what she perceived as a delay by Nike in publicly backing the Black Lives Matter movement. “Me speaking up against these injustices is not because I’m against Nike, let me be clear about that,” she said. “It’s because I know they can do better, and they have the opportunity to change the world.”

In a statement that month, Nike said the company “respects people’s right to peacefully protest”, adding that despite progress in developing a diverse and inclusive workplace, “we have a lot more work to do”. A letter to employees from Donahoe over the summer was more explicit. “What I have learned is that many have felt a disconnect between our external brand and your internal experience,” he wrote. “You have told me that we have not consistently supported, recognised and celebrated our own Black teammates in a manner they deserve. This needs to change.”

The internal discord persisted as Nike continued to develop progressive advertisements, including a campaign featuring LeBron James and soccer star Megan Rapinoe saying, “We have a responsibility to make this world a better place.” Before its release, some members of the diversity working group privately objected. They believed that Nike should hold off on consumer-facing social-justice campaigns until it had publicly addressed internal shortcomings. Wilkins, the spokesman, reiterates Nike’s commitment to improving diversity among all under-represented groups, “with a sharp focus on black, Latinx and women” employees.

For all of the recent changes, Nike’s essential tensions will persist into the next era: balancing its power as a global retailer and its formidable influence in style, social messaging and the culture at large. “I don’t envy the task of trying to keep the largest sportswear company in the world cool,” says Kahn, the co-author of Sneakers. “Their image is everything. If people don’t think they’re cool, it’s over for them.”

Sara Germano is the FT’s US sports business correspondent

Follow @FTMag on Twitter to find out about our latest stories first. Listen to our podcast, Culture Call, where FT editors and special guests discuss life and art in the time of coronavirus. Subscribe on Apple, Spotify, or wherever you listen.